Teaching AI to Spot Fake XKCD Comics (Part 1)

Building a judge with DSPy and GEPA

This is Part 1 of a two-part series. In this installment, I build a judge that can reliably distinguish real XKCD comics from AI-generated fakes. In Part 2, I'll use GEPA to optimize a prompt that can generate XKCD-style comics capable of fooling this very judge.

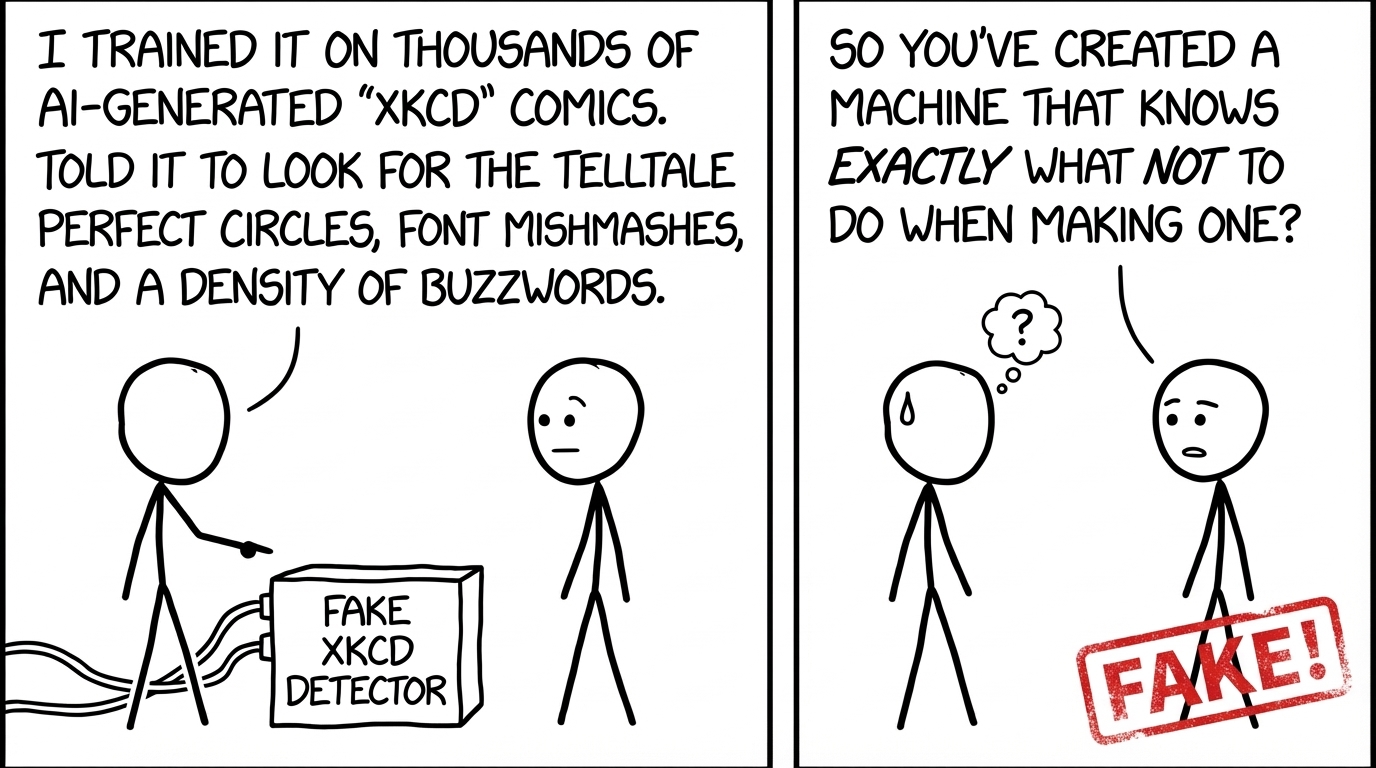

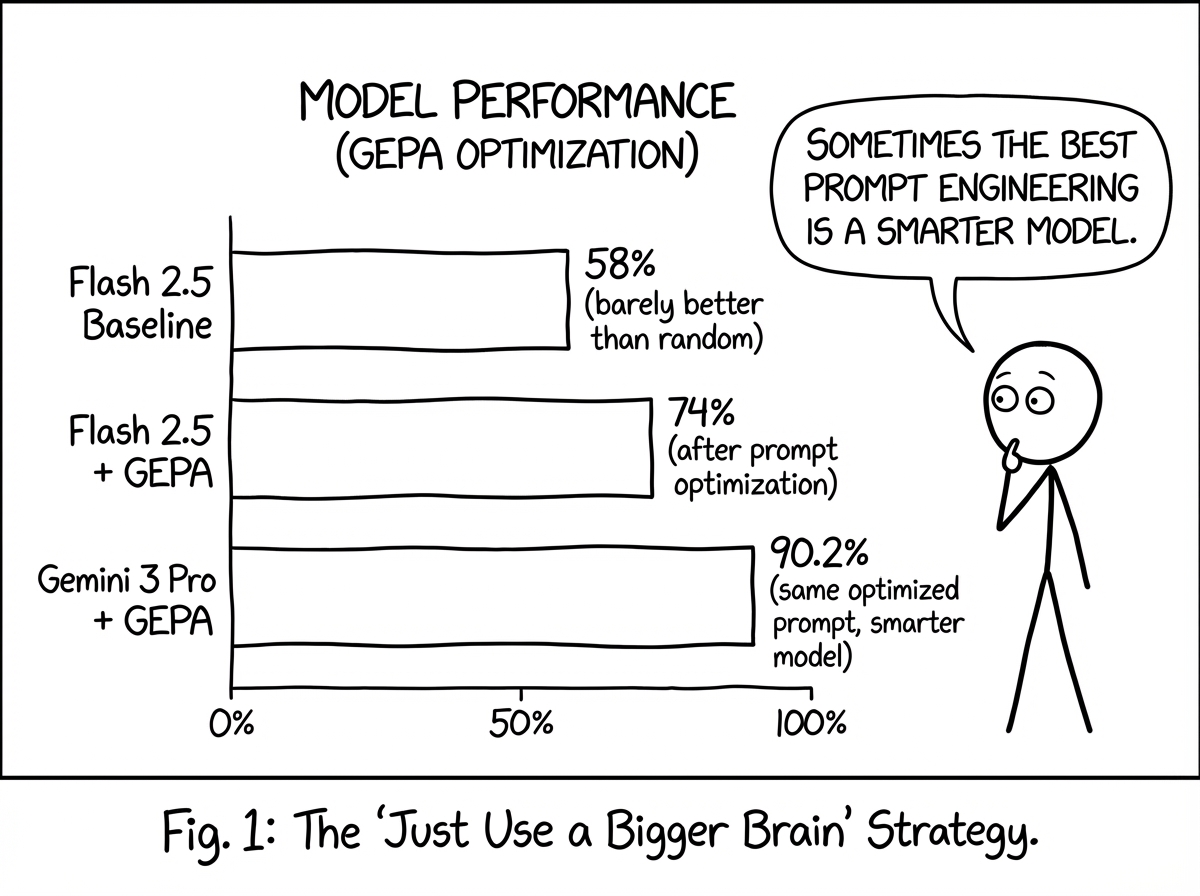

TL;DR: I used GEPA to optimize a prompt for detecting fake XKCD comics. Baseline Gemini 2.5 Flash scored 58%. After GEPA optimization: 74%. Same optimized prompt on Gemini 3 Pro: 90.2%. The optimizer discovered detection heuristics I never would have written myself, like checking for "font mixing" and "geometrically perfect circles."

Can AI spot AI? I built a system that distinguishes genuine XKCD comics from AI-generated fakes using DSPy and GEPA. What started as a simple classification task evolved into an exploration of voting theory, Bayesian inference, and the subtle tells that reveal AI-generated content.

DSPy (GitHub) is a framework from Stanford NLP for programming with language models. Instead of writing prompts by hand, you define typed signatures and modules that the framework compiles into optimized prompts. It's a cleaner way to build LLM applications.

GEPA (Genetic-Pareto), from Lakshya Agrawal et al., is a prompt optimizer that uses natural language reflection to learn from trial and error. It runs your model on examples, reflects on failures, proposes better prompts, and keeps what works. The paper shows it outperforming reinforcement learning approaches while using far fewer samples. GEPA is integrated into DSPy as an optimizer.

The Challenge: Spotting Fakes in a Sea of Stick Figures

XKCD comics have a deceptively simple style: stick figures, minimal line art, and hand-lettered text. But that simplicity makes them surprisingly hard to fake. Every wobble in Randall Munroe's lines carries intention. Every imperfect circle of a stick figure's head is authentically human.

I generated 115 fake XKCD-style comics using Gemini 3 Pro Image (codename "Nano Banana Pro") across a variety of topics: programming, physics, math, relationships, and more.

The fakes were impressive. They captured the general aesthetic, the tech humor, even some of the panel layouts. But could an AI learn to spot its own kind?

Test Your Skills: Human vs Machine

Before we dive into how GEPA learns to spot fakes, try it yourself. Below are real pairs from my dataset. One image is a genuine XKCD by Randall Munroe; the other is AI-generated. Can you spot the fake? Tap any image to zoom in, then click "Select as Fake" to make your choice.

Note: The AI-generated fakes you'll see here haven't been optimized yet. They're naive attempts that still contain obvious tells. In Part 2, I'll use GEPA to evolve a generation prompt that produces fakes good enough to fool this very judge.

Evolution of the Approach

From the start, I knew I'd be using GEPA to optimize the judge. GEPA works by running a student model on training examples, then using a smarter reflection model to analyze failures and propose improved prompts. The question wasn't whether to use GEPA, but how to frame the task so GEPA could actually learn something useful.

My first attempt was naive: show the model a single image and ask "is this real or fake?" With a 50% baseline (random guessing), GEPA struggled to make progress. The reflection model had nothing to compare. When the student got an image wrong, there was no context about what made it obviously real or fake.

The breakthrough came when I reframed the problem as pairwise comparison: given two images (one real, one fake), identify which is which. This was crucial for GEPA specifically. Now when the student got a pair wrong, the reflection model could see both images and reason about the differences it should have noticed. The richer context gave GEPA the signal it needed to evolve better prompts.

class XKCDPairSignature(dspy.Signature):

"""Given two comic images, one is a genuine XKCD by Randall Munroe

and one is AI-generated. Identify which is real."""

image_a: dspy.Image = dspy.InputField(desc="First comic image (labeled A)")

image_b: dspy.Image = dspy.InputField(desc="Second comic image (labeled B)")

reasoning: str = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Compare the two images, analyzing: line quality differences, "

"text/lettering consistency, character proportions..."

)

real_image: Literal["A", "B"] = dspy.OutputField(

desc="Which image is the genuine XKCD: 'A' or 'B'"

)I also tried a quad approach: show four images (three real, one fake) and ask the model to find the impostor. With a 25% random baseline, I hoped this harder task would force the model to develop more robust heuristics. It didn't work. Performance was actually slightly worse than pairwise comparison. Sometimes the simpler framing is just better.

GEPA: Teaching AI to See What We Can't Articulate

Here's where it gets interesting. I used GEPA (integrated into DSPy) with a MultiModalInstructionProposer to let the system discover its own detection strategies. The setup:

- Student model: Gemini 2.5 Flash (fast, cheap, the model we're optimizing)

- Reflection model: Gemini 3 Pro (smarter, analyzes failures and proposes improvements)

- Dataset: 100 image pairs with a 20/80 train/eval split

GEPA iteratively refines prompts by running the student on training examples, using the reflection model to analyze failures, proposing improved instructions, and keeping what works on validation.

gepa = dspy.GEPA(

metric=xkcd_pair_metric,

reflection_lm=dspy.LM("gemini/gemini-3-pro-preview", max_tokens=65536),

auto="medium",

track_stats=True,

instruction_proposer=MultiModalInstructionProposer(),

)

optimized_judge = gepa.compile(

student=judge,

trainset=train_set, # 20 pairs

valset=val_set, # 80 pairs

)The Results

That last number is striking. The prompt that GEPA discovered for Flash worked even better when we put a smarter model in the driver's seat. The optimization process surfaced genuinely useful heuristics, not just tricks that happened to work for one model.

The optimized prompts that emerged are fascinating. They reveal detection strategies I never would have articulated:

The "Font Mixing" Tell

The "Smoking Gun" (Font Mixing): This is the single most reliable indicator. Genuine XKCD uses a hand-lettered style for everything: speech bubbles, labels, axis titles, code on screens, and text inside diagrams.

AI Tell: If you see a standard digital font (e.g., Arial, Sans-Serif, Courier) used for labels or computer screens while speech bubbles are hand-lettered, it is AI.

The "Geometric Perfection" Tell

Geometric Perfection (The "Smoking Gun"): AI models struggle to replicate human imperfection. If a comic features stick figure heads that are mathematically perfect circles, it is the fake. Authentic XKCD heads are hand-drawn, irregular loops or "potatoes."

The "Buzzword Salad" Tell

Concept Density: AI attempts to sound "nerdy" by cramming as many technical keywords as possible into one strip (e.g., "SSH," "Kernel," "AWS," "API," "DRM," "Buffer Overflow" all at once). It creates a "word salad" of tech terms. Genuine XKCD usually focuses on one specific concept and explores it deeply.

These excerpts are from the optimized prompt that GEPA discovered. The XKCDPairSignature shown earlier is the signature that gets optimized: GEPA fills in detailed instructions for the reasoning field based on what it learns from failures.

The Voting Experiment (That Didn't Work)

I'd been reading about MAKER, a recent paper where researchers solved a million-step Towers of Hanoi problem with zero errors using voting. Their approach was clever: break tasks into tiny atomic steps, then use "first-to-ahead-by-k" voting to catch errors before they propagate. The math works out nicely: if your per-step accuracy is high enough and errors are independent, you can vote your way to near-perfect reliability.

With 74% accuracy from Gemini 2.5 Flash, I figured I'd try the same thing. The theory is straightforward: run the judge multiple times, and if errors are random, the correct answer should win more often than not.

I implemented a few voting strategies:

- Majority voting: Run N times, take the most common answer

- First-to-ahead-by-k: Keep sampling until one answer leads by k votes (the MAKER approach)

- Bayesian stopping: Stop when posterior confidence crosses a threshold

It didn't really work. I was seeing maybe a 4% boost before I cut the experiment short. Not worth the extra API calls.

Looking back, I think I misunderstood when voting helps. MAKER worked because Towers of Hanoi has a key property: each step is a simple, atomic decision with a clear right answer, and the model's errors are basically random noise. My problem was different. When Flash got confused about whether an image was real or fake, it wasn't random confusion. It was getting fooled by the same things repeatedly. The model would see a convincingly hand-drawn fake and pick it as real five times in a row. Voting doesn't help when errors are correlated like that.

The MAKER paper actually addresses this with "red-flagging," discarding outputs that look suspicious. But for image classification, I didn't have a good way to know which outputs to distrust. In the end, using Gemini 3 Pro with the GEPA-optimized prompt just worked better (90.2%) than trying to vote my way out of Flash's limitations.

Key Implementation Details

A few technical notes that made a difference:

- Use images from comic #500+: Earlier XKCD comics had a different, rougher style that confuses the model. I filtered to only use comics after #500 for consistency.

- Balance your training data: Ensure equal distribution of "A is real" vs "B is real" examples to prevent position bias. The model should learn image features, not position preferences.

- MultiModalInstructionProposer is key: For image tasks, you need DSPy's multimodal instruction proposer so GEPA can reason about visual features, not just text.

# The multimodal proposer lets GEPA reason about images

from dspy.teleprompt.gepa.instruction_proposal import MultiModalInstructionProposer

gepa = dspy.GEPA(

metric=xkcd_pair_metric,

instruction_proposer=MultiModalInstructionProposer(),

...

)What's Next

A few things stuck with me from this project. The optimized prompts picked up on stuff I wouldn't have thought to check for, like how real XKCD uses hand-lettering everywhere, even for code on computer screens. GEPA found that; I didn't. There's something interesting about using AI to figure out what AI gets wrong.

The prompt also transferred well between models. I optimized it on Flash 2.5 (74% accuracy), but when I ran the same prompt on Gemini 3 Pro, it hit 90.2%. That was a nice surprise. The heuristics GEPA discovered weren't just model-specific tricks.

For Part 2, I'm going to flip this around. Instead of optimizing a judge, I'll use GEPA to optimize a generation prompt, one that produces XKCD-style comics good enough to fool the judge I just built. Can the generator learn to avoid perfect circles and font mixing? We'll see.